Imagine wrapping yourself in a garment that speaks without words. It tells a story of seasons, of meticulous artistry, and of centuries-old tradition. The kimono is not merely clothing; it is a canvas of Japanese culture, worn with grace and preserved with love. Whether you are a long-time admirer of Japanese aesthetics or a newcomer captivated by the silken folds, understanding the depth behind the kimono transforms the experience of wearing one.

In this guide, we explore the rich tapestry of history woven into every thread, the dedication of the artisans who create them, and practical advice on how to select and care for your very own piece of wearable art.

More Than Fabric: The Soul of the Kimono

The word kimono literally translates to “thing to wear,” but its simplicity in name belies its complexity in significance. For over a thousand years, the kimono has evolved from a practical undergarment during the Heian period (794–1185) to the sophisticated outer robe we recognize today.

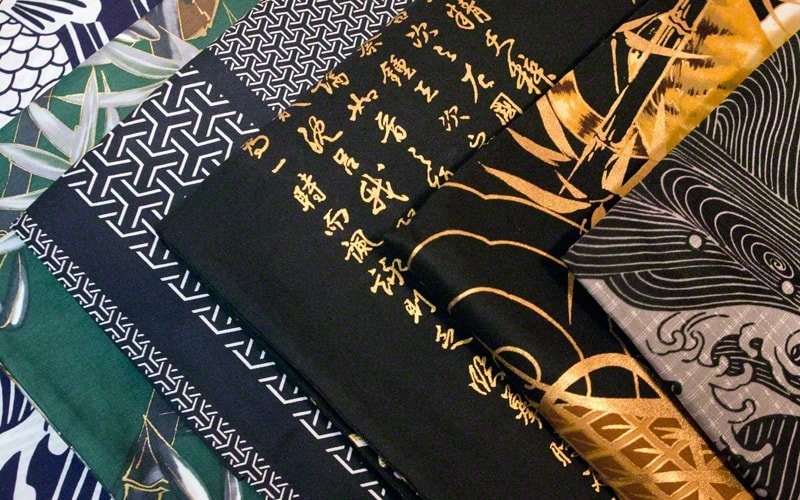

It is a garment that rejects the Western concept of tailoring to fit the body’s curves. Instead, the kimono is cut from a single bolt of fabric, or tanmono, in straight lines. The beauty lies in how it wraps the wearer, creating a uniform, cylindrical silhouette that emphasizes posture and grace. This design philosophy reflects a cultural appreciation for flat planes of fabric, which serve as uninterrupted surfaces for breathtaking artistic expression.

The Artisan’s Touch

True luxury lies in the details you cannot rush. The creation of a traditional kimono is a labor of love that involves a symphony of specialized craftsmen.

- Dyers (Some-shi): Using techniques like Yuzen, artisans hand-paint intricate designs directly onto the silk, resisting dyes with rice paste to create crisp, vibrant patterns that look like paintings.

- Weavers (Ori-shi): In styles like Oshima Tsumugi, the pattern is dyed into the threads before weaving. The weaver must align each thread with microscopic precision to reveal the image—a process that can take months for a single roll of fabric.

- Embroiderers (Nui-haku): To add texture and opulence, gold and silver threads are often embroidered over the dyed patterns, catching the light with every movement.

When you purchase a quality kimono, you are supporting a lineage of skills passed down through generations.

Decoding the Occasion: When to Wear What

One of the most intimidating aspects for newcomers is the strict code of formality surrounding kimonos. The type of kimono you wear communicates your age, marital status, and the formality of the event. Wearing the right kimono shows respect for the host and the occasion.

The Furisode: Youthful Vibrance

Recognizable by its long, flowing sleeves that can touch the ground, the Furisode is the most formal kimono for unmarried women. It is vibrant, often featuring bold, sweeping patterns across the entire garment. You will typically see these at Coming of Age Day ceremonies (Seijin no Hi) or weddings.

The Tomesode: Elegant Maturity

For married women, the Tomesode is the pinnacle of formality. The Kuro-tomesode (black base) is worn by mothers of the bride or groom at weddings. It features five family crests (kamon) and an elegant pattern that appears only below the waist, symbolizing a humble yet dignified presence.

The Houmongi: Social Grace

Translating to “visiting wear,” the Houmongi is a versatile semi-formal kimono suitable for both married and unmarried women. The pattern flows continuously over the seams across the shoulders and sleeves. It is the perfect choice for tea ceremonies, friends’ weddings, or high-end parties.

The Yukata: Casual Comfort

In the heat of summer, the silk is swapped for cotton. The Yukata is the most accessible entry point into the world of kimono. Originally a bathrobe, it is now the standard attire for summer festivals (matsuri) and firework displays. It is casual, comfortable, and fun to accessorize.

Choosing Your Perfect Kimono

Selecting a kimono is a personal journey. While rules exist, your connection to the garment matters most. Here is how to find the one that speaks to you.

1. Let the Season Guide You

Japanese culture places immense importance on the changing seasons. Your kimono should reflect the time of year, often anticipating the coming season rather than the current one.

- Spring: Look for cherry blossoms (sakura), peonies, or butterflies in soft pastels.

- Summer: Choose lightweight weaves like ro or sha featuring water motifs, goldfish, or hydrangeas to evoke coolness.

- Autumn: Rich hues of orange and brown with maple leaves, chrysanthemums, or bush clover are traditional.

- Winter: Pines, bamboo, and plum blossoms (the “Three Friends of Winter”) are classic motifs, often on heavier, lined silk (awase).

2. Consider the Height and Size

While kimonos are adjustable, they are not one-size-fits-all. Vintage kimonos, in particular, tend to be shorter. Ensure the length is roughly equal to your height. If the kimono is too short, it will be difficult to create the ohashori (the fold at the waist).

3. Trust Your Instincts

Are you drawn to bold geometric patterns from the Taisho era, or the subtle, monochromatic elegance of an Iromuji? The right kimono will make you feel confident and poised. Don’t be afraid, match your personality to a pattern.

Caring for Your Kimono

A well-cared-for kimono can last with proper handling. Silk and cotton are natural fibers; they breathe and react to their environment. Proper maintenance is essential to preserving its luster.

- Air it Out: After wearing your kimono, hang it on a kimono hanger (emonkake) indoors, away from direct sunlight, for several hours. This allows body heat and moisture to escape before storage.

- Fold Correctly: Never hang a kimono for long-term storage, as the weight will distort the shape. Learn the proper folding technique (hon-tatami) to ensure creases only appear where they are supposed to be.

- Breathing Room: Store your kimono in a tatooshi (a heavy washi paper wrapper) inside a paulownia wood chest (kiri-tansu) if possible. The paper and wood regulate humidity, protecting the silk from mold and insects.

Embracing the Tradition

Wearing a kimono is an act of mindfulness. It changes how you move; smaller steps become natural, your back straightens, and your gestures become more deliberate. In a world that often rushes, the kimono invites you to slow down and appreciate the beauty of the moment.

We invite you to visit our shop and experience the fabric for yourself. Whether you are looking for a casual Yukata for the summer or a formal masterpiece for a once-in-a-lifetime event, we are here to help you find the piece that resonates with your spirit.

Ready to find your own piece of history? Explore our latest collection online.